I’m sitting with my face in the sun, a cup of tea and a clementine on the table in front of me. In my head, Leonard Cohen singing, and she brings you tea and oranges that come all the way from China.

Spring, which for so long was a tentative reach, is undeniable now. It presses on me, asserting itself in shades of green: celadon, shamrock, jade. And yet, it’s not just the color that bears weight upon me—it’s the sound.

If I could ascribe body parts / senses to each of the four seasons, it would be like this:

Summer is a nose (strawberries, sunscreen, barbecue)

Autumn is an eye (hillsides lit orange, yellow, red)

Winter is a hand (the feel of cold snow on bare fingertips)

And Spring—Spring is an ear. Gigantic, extended, wide open, listening.

I open every window to better hear it: the richness of returning birdsong. It’s not an alarm that wakes me in the morning, it’s the dawn chorus, the first robin having a laugh as the light lifts.

Hearing the air fill with the sound of the birds again is like hearing the language of my heart. I speak that song. Over the years, I have learned to identify each bird in my area by its unique timbre and collection of notes. I understand the three-note canter of the common yellowthroat, blurred at the edges like wax, and the cheery you’re here! you’re here! of the Baltimore oriole (which I will always think of as a greeting to my son, born in late spring—the exact words I uttered over and over to myself as they placed his purple body on my chest). I heed the sage advice of the Eastern towhee to drink your tea and take another sip of my English Breakfast.

It’s a kind of mother tongue, one that winter separates me from—half the year, when the cold comes and the birds leave, I become an immigrant and almost forget the voice of the land that birthed me. Hearing it again now makes me want to cry. I recognize the language of this season the way someone who speaks Turkish, but is far from home, might suddenly feel their ears perk up at the sound of teşekkürler, might feel themselves seen for the first time in a long time.

To understand the language of the world around you is a kind of homecoming.

Last week, I wrote the first full song I’ve written in nearly two years. It has felt so shameful for me to say it, to stare directly at it, this long absence of songwriting. I’ve never gone nearly so long without it—I’m used to being called “prolific.” I teach a songwriting workshop. It’s supposed to be in my blood, a core facet of my identity. Where did the sound go?

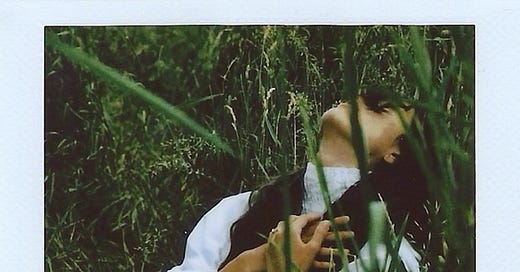

I think, in part, writing my last album See You At The Maypole took everything out of me. It felt like the thing I was trying to write my whole career, and when it was done being written, I reached the end of a long road, and I sat down in the grass, and I could go no further.

I think, in part, becoming a mother took everything out of me. It reshaped and shook me up, it reoriented my sense of time and reconfigured my energy. My old creative habits and practices went out the window. I lost access to what came before, and I understood that my tools for writing had to change just as profoundly as I had changed, but I didn’t know how.

And then, the birds returned.

And I wrote a song—a song about seasons and nature and the seismic clash of being an artist and mother—and it felt so good to hear that language again. It felt like remembering my mother tongue. It felt like a homecoming.

It’s not a life-altering song. It’s not a masterpiece. It’s not the start of a new album or even really meant to be shared. It’s just a little green reach into space, and I trust enough to know that soon, if I let it, if I stay open to the rhythms and cycles of things, that color will infuse everything again, asserting itself into every corner of my life, pressing against me like a living thing.

Oh, every bird is singing at me,

Saying, there’s a season to be silent, it’ll pass,

And it is good. We live into the empty spaces,

Tunneling through mud yet never crushed beneath the weight.

And I am here to tell you it’s alright,

Splitting like an atom—it’s a fission, it’s a rite.

And I am hung like laundry on the line,

Snapping in a spring breeze, dark divided from the light.

And you are mine, dandelion in the air,

Borne upon a current til you’re scattered everywhere.

And you are yours, leaving smudges on the glass,

Pressing to get outside where the sun is setting fast.

And you are here,

And the moon is in your hair.

When River was born, I was so entranced by his ears. Seashell ears, I called them. Each a miniature nautilus, an infinite fractal repeating. An entire universe contained in those organs. What was he hearing, there in those first hours when he was separated from my body? What cosmic whoosh, what song, still thrummed through him?

My old college professor, the composer Brian Harnetty, has a beautiful way of reframing the way we talk about listening. Listening with, he proposes we say. Not listening to. We are listening with the environment, harmonizing in every second we bend our ear in that direction. Active ears not just attuned to the world, but collaborating with it.

In a conversation Harnetty did in 2023 with the great writer and botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, Kimmerer responds delightfully to this concept of listening with by saying that yes, even the environment is listening with itself. You can, in fact, measure it: the way the stomates, the pores, on the leaves actually open in the presence of birdsong. They have ears that widen just like ours. The leaves are listening too.

What happens when we start to imagine and organize our lives this way: as a kind of collective listening, tuning into the details that might otherwise go unheard? What kind of world becomes possible when we can move through the land and understand that we are a part of it?

The birds help me remember that the language of our hearts is innate. Our pores open to it, receive it, suck it in like light.

They remind me that when I am most lost and far from myself, I can listen with the world around me and recognize the tongue, and in doing so, find my way back home.

These beloved birds remind me that all is cyclical, that sometimes seasons are long, but that there is always song on the other side of it.

Will you listen with me?

Thank you for yet another gorgeous essay that speaks so directly to my heart, the questions I am holding and walking with in this very moment. My baby is four months old now and I am in full devotion as a mother, saying goodbye to time alone to write and make music, and reading this reassures me that all is well - that the seasons of life are turning perfectly, and that bird song returns each spring. I really love your writing.