On trees and selkies: a year-end reflection

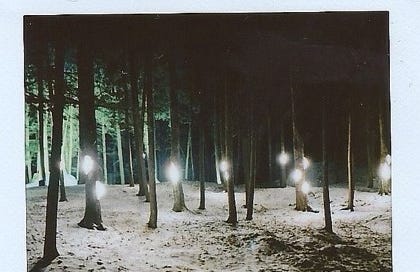

Every year, we get a Christmas tree and name it Bemidji. This began three years ago, when we were watching the TV show Fargo over the holidays and fell in love with the name of a town they mentioned. I thought it was fictional and was thrilled to learn it’s a real place in Minnesota. Now we’re on Bemidji III. We laugh about how someday, when we have kids, they’ll grow up thinking Christmas trees are called Bemidjis. And when they get even older, they’ll wonder why their parents were so weird. As ever, I am delighted by the power of naming things, of teaching those names to others, of passing on new traditions. Our language is elastic, our minds a bouncy castle of word association and memory, slamming disparate parts together. Incredible how a Minnesotan town can became a cut balsam shining with lights.

Something was wrong with Bemidji III from the start. She never took up water. We read that sometimes trunks get clogged with sap, preventing uptake, so we filled the stand with hot water to try to soften the blockage. It didn’t work. The pores remained clamped, as if in protest. She simply would not drink. The tree sags and sags, shedding needles in fistfuls. Ornaments threaten to slide right off. I feel sad when I look at her, this radiant conifer felled for our enjoyment. I don’t blame her for revolting.

I recently re-read a story about the myth of the selkie. In Celtic mythology, selkies were beautiful seal-women who shed their skins under the moonlight, revealing their human form. The story goes that one day a man came upon a group of selkies bathing under the moon and, wanting to take one for a wife, stole one of their velvety skins to trap her on land. The other selkie sisters dove back into the sea, but the one without her skin could not join them. She married the man, with whom she bore many children, and never swam as her seal-self again.

I understand, in this story, the sorrow of the Bemidjis. Uprooted from their forest homes and forced to stand in our living rooms, heavy with baubles and lights. I also understand it on a more personal level.

Last December, I too faced a forced separation from a part of myself when I suffered a miscarriage. I woke, disoriented, to a lifeless, snow-covered world. I wished I could go back to who I was, but I was trapped in a new reality. I wondered how I’d adapt. As I looked ahead to the expanse of months before me, I remember thinking, “What if this year doesn’t make me stronger, it just makes me sadder?”

Now, on the other end of the year, I see what the author and Jungian analyst Lisa Marchiano means when she offers a reinterpretation of the selkie myth. Perhaps the selkie, she suggests, needed to make the change to land as a way to grow, to experience all of what life has to offer. As a shapeshifter, she was living half in one world, half in the other—a fantasy. The transition to land marked her transition into the responsibilities and rich experiences of adulthood, marriage, and motherhood. “Selkie women dream of running away,” Marchiano writes, “but [they are] presented with the opportunity to grow by becoming more grounded.” What does it mean to stay—to stay even when it’s hard—to truly commit to the path of our growth? What can we learn in this place of groundedness?

I see now that I am stronger, and that part of me is sadder, in that I've traveled to a more distant edge of sadness—the far edge where the land meets the sea. But I am also so much more joyful and so much more alive. There is a vividness, an intensity, a sharpness that extends to the gratitude and wonder I feel at where life has brought me now. So no, I can’t go back to who I was. That skin was shed and stolen away. The reckoning felt violent at the time, but it was actually a benevolent gift. I have learned to stay, to love, and to live in this new landscape.

Maybe the same can’t be said of our Bemidji. Soon, we’ll unburden her of her load and lay her down at the back of the yard with her sisters, Bemidjis I and II. A small attempt to return her to her kind. But I take solace in knowing that nature will collect her back into the fold as she breaks down to parts, needles grinding with time into mulch, turning once again into the soil that will feed the forest.

—

For more content, including unreleased music, creative process videos, and exclusive livestreams, subscribe to my Patreon here! We’ve been building a whole community over there since 2020, and we’d love to have you. I’m so deeply grateful for the support.